Calf muscle bruising represents one of the most common yet potentially concerning symptoms that can affect individuals across all age groups and activity levels. From professional athletes experiencing direct trauma during competition to elderly patients developing spontaneous discolouration due to underlying medical conditions, the appearance of bruising on the posterior leg requires careful evaluation and understanding. The complexity of the calf’s anatomical structure, combined with its rich vascular network and susceptibility to various pathological processes, makes proper assessment essential for determining appropriate treatment pathways and identifying potentially serious underlying conditions that may require immediate medical intervention.

Anatomical structure and vascular network of the calf muscle complex

Gastrocnemius and soleus muscle composition

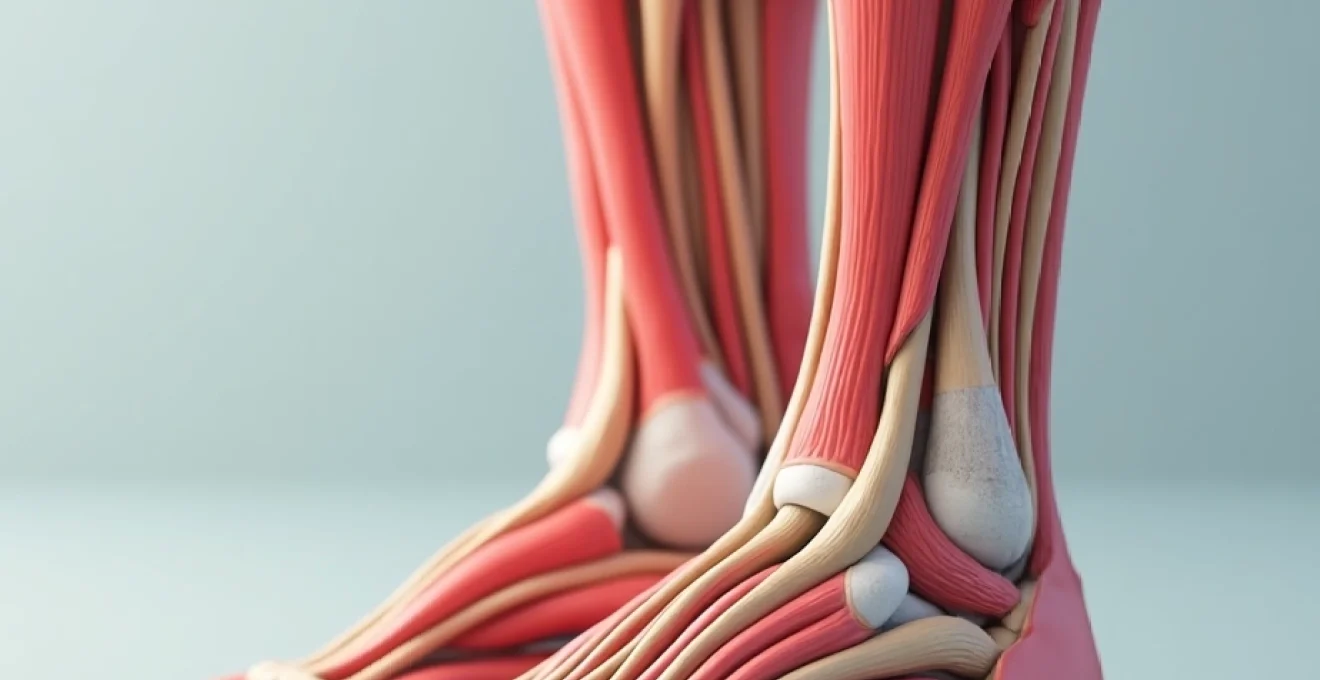

The calf muscle complex consists primarily of two major muscle groups that work synergistically to facilitate lower limb movement and provide propulsive force during locomotion. The gastrocnemius muscle, positioned superficially, forms the prominent bulge visible beneath the skin and comprises two distinct heads—medial and lateral—that originate from the femoral condyles. This powerful muscle extends distally to merge with the deeper soleus muscle, creating the robust Achilles tendon that attaches to the calcaneus.

The soleus muscle, lying beneath the gastrocnemius, originates from the posterior aspects of the tibia and fibula, providing sustained postural support and contributing significantly to venous return through its pumping action. Together, these muscles create a complex three-dimensional architecture that houses an extensive network of blood vessels, making the region particularly susceptible to bruising when subjected to trauma or underlying vascular pathology. The intricate arrangement of muscle fibres, fascial planes, and vascular structures creates multiple potential spaces where blood can accumulate following injury or vessel rupture.

Posterior tibial and peroneal artery distribution

The arterial supply to the calf muscles demonstrates remarkable complexity, with multiple vessels contributing to the rich vascular network that nourishes these metabolically active tissues. The posterior tibial artery serves as the primary source of blood supply, giving rise to numerous muscular branches that penetrate deep into both the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. These vessels follow specific anatomical pathways, creating predictable patterns of bruising when damaged through trauma or pathological processes.

The peroneal artery, running along the lateral aspect of the posterior compartment, provides additional arterial supply through perforating branches that communicate with the posterior tibial system. This dual arterial supply creates a robust circulation that can maintain tissue viability even when one system becomes compromised, but also increases the potential for significant bleeding when multiple vessels are affected simultaneously. Understanding these arterial patterns proves crucial for healthcare professionals when evaluating the extent of injury and predicting potential complications associated with calf muscle bruising.

Venous drainage through saphenous and deep venous systems

The venous drainage of the calf region involves both superficial and deep systems that work collaboratively to return blood to the central circulation. The superficial venous system, comprising the great and small saphenous veins, collects blood from the skin and subcutaneous tissues through an extensive network of tributaries. These vessels can become dilated and tortuous in conditions such as chronic venous insufficiency, leading to increased susceptibility to bleeding and subsequent bruising.

The deep venous system, including the posterior tibial, peroneal, and popliteal veins, handles the majority of venous return from the calf muscles themselves. These vessels contain numerous valves that prevent backflow and rely heavily on the muscle pump mechanism for effective drainage. When this system becomes compromised through thrombosis, valve dysfunction, or external compression, venous congestion can develop, leading to increased capillary fragility and spontaneous bruising. The interconnections between superficial and deep systems through perforating veins create additional pathways for bleeding and bruise formation when these communications become disrupted or dysfunctional.

Fascial compartments and tissue architecture

The calf region contains multiple fascial compartments that house different muscle groups and neurovascular structures within distinct anatomical boundaries. The posterior compartment, divided into superficial and deep sections by the transverse intermuscular septum, creates separate spaces that can independently develop bleeding and bruising patterns. The superficial posterior compartment contains the gastrocnemius and plantaris muscles, while the deep compartment houses the soleus, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus, and tibialis posterior muscles.

These fascial boundaries play a critical role in determining the distribution and extent of bruising following injury or pathological bleeding. When bleeding occurs within a specific compartment, the rigid fascial walls can contain the haematoma, leading to increased pressure and potentially compromising circulation to the contained structures. Conversely, bleeding that occurs across compartmental boundaries may create more extensive but potentially less dangerous bruising patterns. Understanding these anatomical relationships becomes essential when assessing the severity of calf muscle bruising and determining appropriate management strategies.

Traumatic injuries leading to calf muscle bruising

Direct impact contusions from sports and accidents

Direct trauma to the calf muscles represents the most straightforward mechanism for developing visible bruising, with contact sports and vehicular accidents serving as primary sources of such injuries. The mechanism typically involves a blunt force impact that compresses the muscle tissue against the underlying bone, causing disruption of small blood vessels within the muscle fibres and surrounding connective tissue. The severity of resulting bruising depends on multiple factors, including the force of impact, the area affected, and the individual’s underlying vascular health.

In athletic contexts, direct contusions commonly occur during activities such as football, rugby, and martial arts, where participants may receive kicks or impacts from equipment or opposing players. The immediate appearance of swelling and discolouration provides clear evidence of tissue damage, with the bruising pattern often reflecting the shape and size of the impacting object. These traumatic contusions typically follow predictable healing patterns, with colour changes progressing from initial red or purple through various shades of blue, green, and yellow as the haemoglobin breakdown products are gradually absorbed by the body’s natural healing processes.

Muscle strain classifications: grade I, II, and III tears

Muscle strains affecting the calf complex create specific patterns of bruising that correlate directly with the severity and extent of tissue damage. Grade I strains involve microscopic tearing of muscle fibres, typically producing minimal visible bruising but causing localised pain and stiffness. These minor injuries may present with subtle discolouration that becomes more apparent 24-48 hours after the initial injury, as inflammatory processes develop and small amounts of blood leak from damaged capillaries.

Grade II strains represent partial muscle tears that create more significant tissue disruption and correspondingly more obvious bruising patterns. The bleeding associated with these injuries often tracks along fascial planes, creating bruising that may appear some distance from the actual injury site. This phenomenon, known as gravitational tracking, can cause confusion in diagnosis as the visible bruising may not accurately reflect the location of the underlying muscle damage. Grade III strains, involving complete muscle rupture, typically produce dramatic and immediate bruising accompanied by severe pain and functional impairment.

Haematoma formation in intramuscular and intermuscular spaces

The development of haematomas within the calf muscles creates distinct clinical presentations that depend on their anatomical location and the extent of bleeding involved. Intramuscular haematomas occur when bleeding remains confined within the muscle fibres themselves, creating a localised collection of blood that may not initially produce visible external bruising. These deeper collections can create significant pain and functional impairment while remaining relatively inconspicuous from an external examination perspective.

Intermuscular haematomas develop when bleeding occurs between different muscle groups or along fascial planes, often producing more dramatic external bruising but potentially causing less functional impairment than their intramuscular counterparts. The blood in these locations can spread more freely, creating extensive discolouration patterns that may extend well beyond the original injury site.

The ability to distinguish between intramuscular and intermuscular haematomas proves crucial for determining appropriate treatment strategies, as intramuscular collections may require more aggressive management to prevent complications such as compartment syndrome or chronic fibrosis.

Tennis leg syndrome and plantaris muscle rupture

Tennis leg syndrome represents a specific type of calf muscle injury that commonly affects recreational athletes, particularly those participating in racquet sports and similar activities requiring sudden directional changes and explosive movements. This condition typically involves rupture of the plantaris muscle or partial tearing of the medial head of the gastrocnemius, creating characteristic patterns of pain and bruising in the medial aspect of the calf. The sudden onset of severe pain, often described as feeling like being struck by a projectile, distinguishes this injury from more gradual onset conditions.

The bruising associated with tennis leg syndrome often develops over several days, initially appearing deep within the muscle before becoming visible at the surface. The pattern typically follows the anatomical distribution of the affected muscle, with discolouration tracking distally along the medial border of the calf and potentially extending into the ankle and foot regions. Early recognition and appropriate management of this condition can significantly reduce recovery time and prevent the development of chronic complications that might otherwise compromise long-term athletic performance and daily functional activities.

Vascular pathologies causing calf discolouration

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism risk

Deep vein thrombosis affecting the calf region creates a medical emergency that can present with bruising-like discolouration, making accurate diagnosis critically important for preventing potentially fatal complications. The formation of blood clots within the deep venous system disrupts normal circulation, leading to venous congestion, increased capillary pressure, and subsequent bleeding into surrounding tissues. The resulting discolouration may initially appear similar to traumatic bruising but typically demonstrates different characteristics in terms of distribution, colour intensity, and associated symptoms.

The risk of pulmonary embolism significantly increases when calf deep vein thrombosis remains undiagnosed or inadequately treated, as clot fragments can dislodge and travel to the pulmonary circulation. This potentially life-threatening complication emphasises the importance of maintaining high clinical suspicion for DVT in patients presenting with calf discolouration, particularly when accompanied by swelling, warmth, and tenderness. Recent research indicates that up to 10% of patients initially diagnosed with calf muscle strains actually have underlying thrombotic conditions, highlighting the need for careful differential diagnosis in cases of unexplained calf bruising.

Chronic venous insufficiency and varicose vein complications

Chronic venous insufficiency creates long-term changes in the calf region that predispose to recurrent bruising episodes and persistent discolouration patterns. The failure of venous valves to maintain unidirectional blood flow leads to sustained elevated pressures within the superficial and deep venous systems, causing progressive dilation of vessels and increased capillary fragility. Patients with this condition often experience spontaneous bruising with minimal trauma, as the compromised vessels are more susceptible to rupture under normal physiological stresses.

Varicose veins represent a visible manifestation of chronic venous insufficiency that can directly contribute to calf bruising through vessel rupture or bleeding from associated skin changes. The tortuous, dilated vessels are particularly vulnerable to trauma, and even minor impacts can cause significant bleeding and subsequent bruising. Additionally, the chronic inflammation associated with venous insufficiency leads to skin changes including hyperpigmentation, lipodermatosclerosis, and increased susceptibility to ulceration, all of which can present with discolouration that may be mistaken for traumatic bruising.

Superficial thrombophlebitis in saphenous veins

Superficial thrombophlebitis affecting the saphenous venous system creates characteristic patterns of inflammation and discolouration along the course of affected vessels. This condition involves the formation of blood clots within superficial veins, accompanied by significant inflammatory response that produces localised pain, warmth, and erythema. The linear pattern of discolouration typically follows the anatomical course of the affected vein, creating a distinctive appearance that can help differentiate this condition from traumatic bruising or other pathological processes.

The management of superficial thrombophlebitis requires careful evaluation to exclude extension into the deep venous system, which would significantly increase the risk of complications including pulmonary embolism.

While superficial thrombophlebitis generally carries a more favourable prognosis than deep vein thrombosis, the potential for progression to more serious conditions necessitates appropriate medical evaluation and monitoring, particularly in patients with multiple risk factors for thrombotic disease.

The resolution of discolouration associated with this condition typically follows a predictable timeline, with gradual fading over several weeks as the inflammatory process resolves and normal circulation is restored.

Arterial claudication and peripheral artery disease

Peripheral artery disease affecting the lower extremities can contribute to calf bruising through multiple mechanisms related to compromised circulation and tissue health. The reduction in arterial blood flow leads to chronic tissue hypoxia, making muscles more susceptible to injury and impairing the normal healing response to minor trauma. Patients with significant arterial insufficiency often develop increased capillary fragility, leading to spontaneous bruising or disproportionate bruising responses to minimal trauma.

The ischaemic changes associated with peripheral artery disease can also create chronic discolouration patterns that may be mistaken for bruising, particularly in the distal portions of the affected limb. These changes typically demonstrate different characteristics from acute traumatic bruising, including a more persistent nature, association with other signs of arterial insufficiency such as hair loss and skin temperature changes, and poor healing response to standard treatment measures. Recognition of these patterns becomes crucial for identifying underlying arterial disease and implementing appropriate management strategies to prevent progression to more severe complications.

Systemic medical conditions manifesting as calf bruising

Numerous systemic medical conditions can present with calf bruising as an early or prominent symptom, making recognition of these patterns essential for prompt diagnosis and treatment initiation. Haematological disorders, including various forms of leukaemia, thrombocytopenia, and bleeding disorders, commonly manifest with spontaneous bruising in dependent areas such as the calves and shins. The pattern of bruising in these conditions typically differs from traumatic causes, often appearing spontaneously without clear precipitating events and demonstrating characteristic distributions that reflect the underlying pathophysiology.

Liver disease represents another significant cause of increased bruising tendency, as hepatic dysfunction impairs the production of clotting factors essential for normal haemostasis. Patients with cirrhosis or acute hepatitis may develop extensive bruising patterns throughout the lower extremities, including prominent calf involvement. The bruising associated with liver disease often demonstrates poor healing characteristics and may be accompanied by other signs of hepatic dysfunction including jaundice, ascites, and spider angiomata.

Autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis can contribute to calf bruising through multiple mechanisms, including the direct effects of the underlying disease process and the side effects of medications used in treatment. Corticosteroids, commonly prescribed for inflammatory conditions, significantly increase bruising susceptibility by causing capillary fragility and impaired wound healing.

The recognition of medication-induced bruising becomes particularly important in patients receiving long-term immunosuppressive therapy, as the altered healing response may mask other serious conditions requiring prompt medical attention.

Nutritional deficiencies, particularly vitamin C and vitamin K deficiency, can create substantial increases in bruising tendency that may first become apparent in the calf region. Scurvy, resulting from severe vitamin C deficiency, creates characteristic bleeding patterns including extensive bruising, petechial rashes, and poor wound healing. Vitamin K deficiency, more commonly seen in patients with malabsorption disorders or those taking anticoagulant medications, impairs the normal clotting cascade and leads to increased bleeding tendency with subsequent bruising formation.

Clinical assessment and diagnostic imaging protocols

The clinical evaluation of calf muscle bruising requires a systematic approach that considers both the immediate presentation and potential underlying conditions that might contribute to the observed findings. The initial assessment begins with a comprehensive history that explores the circumstances surrounding the bruising development, including any remembered trauma, recent changes in activity level, medication use, and family history of bleeding disorders. The temporal relationship between any precipitating events and the appearance of bruising provides crucial information for determining the likely underlying cause and guiding subsequent diagnostic investigations.

Physical examination focuses on characterising the bruising pattern, including its size, shape, colour, and distribution relative to anatomical landmarks. The presence of associated findings such as swelling, warmth, tenderness, and functional impairment provides additional diagnostic information that can help differentiate between various potential causes. Palpation of the affected area may reveal underlying masses or areas of fluctuance that suggest haematoma formation, while assessment of distal

pulses and neurological function can help identify complications that might require urgent intervention.

Diagnostic imaging plays an increasingly important role in the evaluation of calf muscle bruising, particularly when the clinical presentation suggests underlying pathology or when traumatic injuries fail to respond to conservative management. Ultrasound examination serves as the initial imaging modality of choice for most cases, providing real-time visualization of muscle architecture, haematoma formation, and vascular flow patterns. The non-invasive nature of ultrasound, combined with its ability to differentiate between solid and liquid components within tissues, makes it invaluable for distinguishing between simple bruising and more complex pathological processes.

Magnetic resonance imaging offers superior soft tissue contrast and can provide detailed information about the extent of muscle damage, the presence of fluid collections, and the involvement of surrounding structures. MRI becomes particularly valuable when evaluating chronic or recurrent bruising patterns that might suggest underlying structural abnormalities or when surgical intervention is being considered. The ability to visualize tissue characteristics in multiple planes allows for comprehensive assessment of injury severity and can help guide treatment decisions in complex cases.

Computed tomography may be indicated when bony involvement is suspected or when evaluating for complications such as compartment syndrome. The rapid acquisition times and widespread availability of CT make it useful for emergency situations where immediate diagnosis is required. However, the radiation exposure and limited soft tissue contrast resolution make it less suitable for routine evaluation of isolated calf muscle bruising.

Laboratory investigations complement imaging studies by providing information about underlying systemic conditions that might predispose to bruising. Complete blood count, coagulation studies, liver function tests, and vitamin levels can help identify haematological disorders, clotting abnormalities, or nutritional deficiencies that contribute to increased bruising tendency.

Emergency warning signs requiring immediate medical intervention

Recognizing the emergency warning signs associated with calf muscle bruising can mean the difference between successful treatment and life-threatening complications. The development of severe, unrelenting pain that appears disproportionate to the visible injury should raise immediate concern for compartment syndrome, a surgical emergency that can result in permanent disability if not promptly addressed. This condition occurs when bleeding or swelling within the rigid fascial compartments creates pressure that compromises circulation to muscles, nerves, and other vital structures.

Signs of deep vein thrombosis accompanying calf bruising require immediate medical evaluation due to the risk of pulmonary embolism. The combination of unilateral leg swelling, warmth, redness, and tenderness, particularly when occurring in patients with known risk factors such as recent surgery, prolonged immobilization, or malignancy, necessitates urgent diagnostic evaluation and potential anticoagulation therapy. The Wells score and other clinical prediction rules can help healthcare providers assess the probability of thrombotic disease, but definitive diagnosis typically requires imaging confirmation.

Rapid expansion of bruising patterns, especially when accompanied by signs of hemodynamic instability such as tachycardia, hypotension, or altered mental status, may indicate significant internal bleeding requiring immediate intervention. This scenario is particularly concerning in patients taking anticoagulant medications or those with known bleeding disorders, as the normal hemostatic mechanisms may be impaired. The development of pulsatile masses within areas of bruising could suggest vascular injury with pseudoaneurysm formation, requiring urgent vascular surgical consultation.

Neurological symptoms accompanying calf bruising, including numbness, tingling, weakness, or changes in sensation, warrant prompt evaluation to exclude nerve compression or injury. The peroneal nerve, running around the fibular head, is particularly vulnerable to compression from haematomas or swelling in the lateral compartment. Early recognition and treatment of nerve compression can prevent permanent neurological deficits that might otherwise result in chronic disability.

Fever, chills, or signs of systemic illness developing in association with calf bruising may indicate secondary infection or underlying systemic disease requiring immediate treatment. Skin changes including breakdown, ulceration, or signs of necrosis suggest compromised tissue viability and require urgent medical attention to prevent further complications and preserve limb function. The presence of these warning signs transforms what might otherwise be considered a minor injury into a medical emergency requiring prompt and aggressive intervention to prevent serious long-term consequences.