The relationship between blood clots and high blood pressure represents one of the most complex and clinically significant connections in cardiovascular medicine. While many patients assume that high blood pressure leads to clot formation, the reverse relationship proves equally important and potentially more dangerous. Blood clots can indeed cause elevated blood pressure through various mechanisms, creating a cascade of physiological changes that impact multiple organ systems. Understanding this bidirectional relationship becomes crucial for healthcare providers managing patients with thrombotic events, as the implications extend far beyond the immediate site of clot formation. The pathophysiology involves intricate interactions between vascular resistance, cardiac function, and systemic circulation that can fundamentally alter a patient’s haemodynamic profile.

Pathophysiology of blood clot formation and vascular resistance

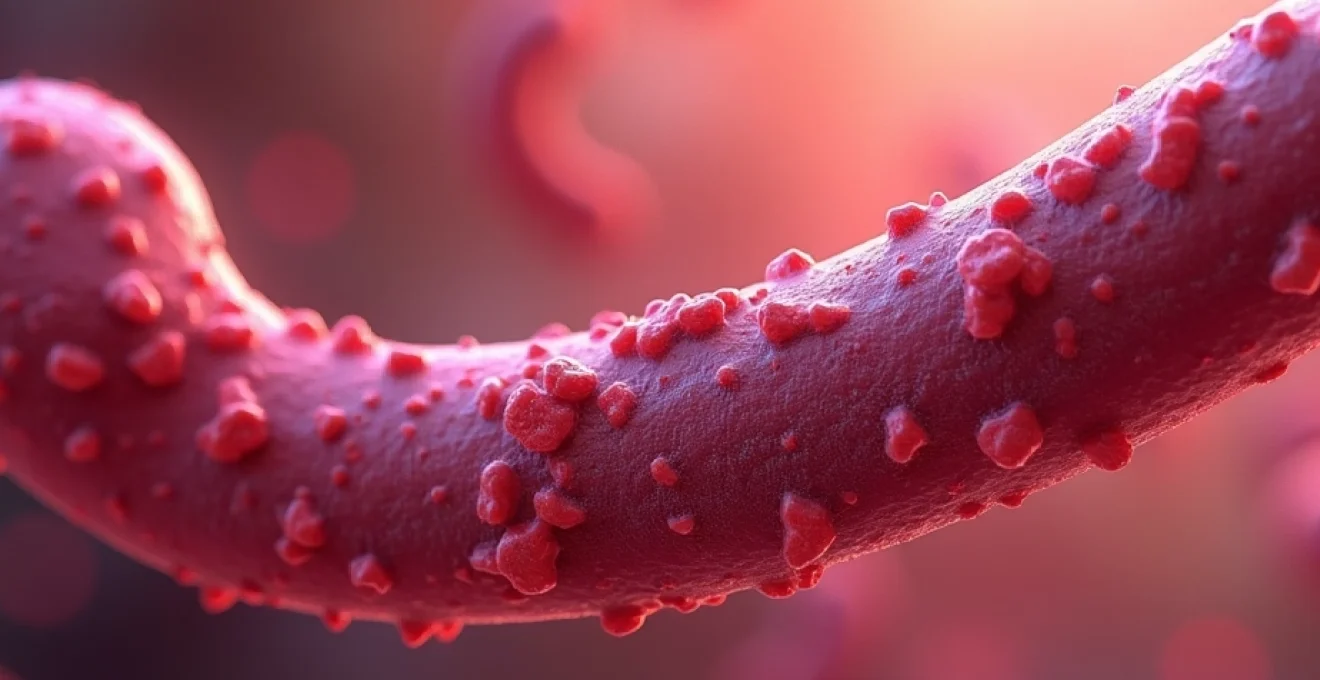

The fundamental mechanism by which blood clots influence blood pressure centres on their impact on vascular resistance and blood flow dynamics. When thrombi form within blood vessels, they create physical obstructions that force the cardiovascular system to work harder to maintain adequate perfusion. This increased workload manifests as elevated systemic blood pressure, particularly when clots affect major vessels or multiple smaller vessels simultaneously. The body’s compensatory mechanisms activate immediately, triggering neurohormonal responses that further contribute to hypertensive changes.

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system plays a pivotal role in clot-induced hypertension, responding to decreased tissue perfusion by releasing hormones that constrict blood vessels and retain sodium. This response, while initially protective, can perpetuate the hypertensive state even after the primary clot resolves. Endothelial dysfunction compounds these effects, as damaged vessel walls lose their ability to produce nitric oxide effectively, reducing their capacity for vasodilation and further elevating blood pressure readings.

Thrombosis-induced endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffening

The formation of blood clots triggers a cascade of inflammatory responses that significantly impair endothelial function throughout the vascular system. Inflammatory mediators released during thrombosis damage the delicate endothelial lining, reducing its ability to regulate vascular tone through nitric oxide production. This dysfunction extends beyond the immediate site of clot formation, affecting arterial compliance and contributing to systemic arterial stiffening . The loss of vascular elasticity forces the heart to generate higher pressures to maintain adequate cardiac output, directly contributing to sustained hypertension.

Research demonstrates that patients with acute thrombotic events show measurable increases in arterial stiffness within hours of symptom onset. The inflammatory cascade includes the release of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules that promote further endothelial damage and perpetuate the hypertensive response. Oxidative stress compounds these effects, creating a self-perpetuating cycle where elevated blood pressure further damages blood vessels, increasing the risk of additional thrombotic events.

Pulmonary embolism impact on right heart pressures and systemic circulation

Pulmonary embolism represents one of the most dramatic examples of how blood clots can acutely elevate blood pressure, though the mechanism differs from systemic arterial hypertension. When clots obstruct pulmonary arteries, they create acute pulmonary hypertension by increasing pulmonary vascular resistance. This elevation in right heart pressures can reach life-threatening levels, with pulmonary artery pressures exceeding 40 mmHg in severe cases. The right ventricle, unaccustomed to such high afterload, struggles to maintain cardiac output, leading to right heart strain and potential failure.

The systemic effects of pulmonary embolism extend beyond the pulmonary circulation, as reduced venous return and impaired cardiac output trigger compensatory mechanisms that can elevate systemic blood pressure.

The body attempts to maintain cerebral and coronary perfusion by activating sympathetic nervous system responses, leading to peripheral vasoconstriction and increased heart rate

. These compensatory responses often persist even after successful treatment of the pulmonary embolism, contributing to sustained hypertension in some patients.

Deep vein thrombosis complications and venous hypertension development

Deep vein thrombosis creates unique haemodynamic challenges that can contribute to both local and systemic blood pressure elevation. When clots obstruct major venous channels, they impair venous return and create venous hypertension in the affected limb. This localised pressure elevation can extend proximally, affecting inferior vena cava pressures and ultimately impacting right heart filling pressures. The reduced venous return compromises cardiac preload, triggering compensatory mechanisms that increase systemic vascular resistance and blood pressure.

Post-thrombotic syndrome, a long-term complication of deep vein thrombosis, perpetuates these haemodynamic disturbances through chronic venous insufficiency. The damaged venous valves and scarred vessel walls create permanent alterations in venous pressure gradients, requiring ongoing cardiovascular adjustments. Studies indicate that patients with post-thrombotic syndrome show significantly higher rates of systemic hypertension compared to age-matched controls, suggesting a causal relationship between chronic venous dysfunction and arterial pressure elevation.

Microthrombi formation in renal vasculature and blood pressure regulation

The formation of microthrombi within renal blood vessels creates particularly concerning implications for blood pressure regulation, given the kidney’s central role in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis. Renal microthrombi can occur as part of systemic thrombotic disorders or as isolated events, but their impact on blood pressure regulation proves disproportionately significant. These small clots impair glomerular filtration, reduce renal blood flow, and trigger the release of renin, initiating a cascade that leads to sustained hypertension.

The kidney’s response to thrombotic injury involves both acute and chronic adaptations that contribute to hypertensive disease. Acute thrombotic events activate the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system, leading to immediate vasoconstriction and sodium retention. Over time, chronic changes in renal architecture and function perpetuate these responses, creating a form of renovascular hypertension that can prove resistant to conventional antihypertensive therapy. The presence of proteinuria and declining glomerular filtration rate often accompanies this form of clot-induced hypertension, providing important diagnostic clues.

Clinical evidence linking thrombotic events to hypertensive episodes

Extensive clinical research has established clear connections between thrombotic events and subsequent hypertensive episodes across diverse patient populations. Large-scale epidemiological studies demonstrate that patients experiencing acute thrombotic events show significantly higher rates of new-onset hypertension compared to control groups, with the relationship persisting years after the initial event. The temporal association between clot formation and blood pressure elevation provides compelling evidence for causality, particularly when accounting for confounding variables such as age, comorbidities, and medication effects.

Hospital-based studies reveal that acute blood pressure elevation occurs in approximately 60-80% of patients presenting with major thrombotic events, including stroke, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism. These pressure elevations often exceed baseline values by 20-40 mmHg systolic, representing clinically significant changes that require immediate management consideration. The magnitude and duration of these pressure elevations correlate with clot size, location, and the degree of vascular obstruction, supporting the mechanistic relationship between thrombosis and hypertension.

Acute coronary syndrome studies: framingham heart study findings

The landmark Framingham Heart Study provided crucial insights into the relationship between coronary thrombosis and blood pressure elevation, tracking thousands of participants over multiple decades. Data from this comprehensive study demonstrate that patients experiencing acute coronary syndrome show immediate and sustained increases in blood pressure that persist well beyond the acute event. The study revealed that coronary thrombosis triggers measurable increases in systemic vascular resistance within hours of symptom onset, contributing to the hypertensive response observed in these patients.

Follow-up data from Framingham participants indicate that the relationship between coronary thrombosis and hypertension extends far beyond the acute phase, with survivors showing significantly higher rates of chronic hypertension development compared to matched controls. The study’s findings suggest that approximately 70% of patients experiencing acute coronary syndrome develop persistent hypertension within five years of their initial event, even after accounting for traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This elevated risk appears related to ongoing endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffening triggered by the initial thrombotic event.

Cerebrovascular accident research from NINDS rt-PA stroke study

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) stroke study provided valuable data on the relationship between cerebral thrombosis and acute hypertensive responses. Patients enrolled in this pivotal study demonstrated that acute stroke, predominantly caused by thrombotic occlusion of cerebral arteries, triggers immediate and dramatic blood pressure elevation in over 80% of cases. The study’s meticulous blood pressure monitoring revealed that systolic pressures frequently exceed 180 mmHg in the acute phase, representing a significant deviation from baseline values.

The NINDS study data also revealed important insights about the temporal relationship between clot dissolution and blood pressure normalisation. Patients who achieved successful recanalisation with rt-PA therapy showed more rapid blood pressure reduction compared to those with persistent arterial occlusion, supporting the hypothesis that ongoing thrombotic obstruction perpetuates hypertensive responses. These findings influenced current stroke management protocols that emphasise careful blood pressure monitoring and gradual pressure reduction following successful thrombolytic therapy.

Portal vein thrombosis case studies and splanchnic hypertension

Portal vein thrombosis represents a unique clinical scenario where venous clots create localised hypertension within the splanchnic circulation, providing insights into the mechanisms by which clots affect regional blood pressure. Case series and observational studies demonstrate that portal vein thrombosis consistently leads to portal hypertension, with pressures rising from normal values of 5-10 mmHg to pathological levels exceeding 12 mmHg. This pressure elevation occurs through direct obstruction of portal venous flow and subsequent development of collateral circulation pathways.

The clinical manifestations of portal vein thrombosis-induced hypertension include splenomegaly, ascites, and variceal formation , demonstrating the systemic effects of localised venous clots. Long-term follow-up studies indicate that approximately 40% of patients with portal vein thrombosis develop chronic portal hypertension requiring ongoing management, even after anticoagulation therapy. These findings highlight how venous clots can create sustained pressure elevations that persist beyond the resolution of the original thrombus.

Antiphospholipid syndrome patient cohorts and secondary hypertension

Patients with antiphospholipid syndrome provide a unique opportunity to study the relationship between recurrent thrombosis and hypertension development, as this autoimmune condition predisposes individuals to multiple thrombotic events over time. Cohort studies following antiphospholipid syndrome patients demonstrate that recurrent thrombotic events correlate with progressive increases in baseline blood pressure, suggesting a cumulative effect of repeated clot formation on cardiovascular function. The prevalence of hypertension in these patient populations exceeds 60%, significantly higher than age-matched controls.

The pattern of hypertension development in antiphospholipid syndrome patients often follows a stepwise progression, with measurable blood pressure increases following each thrombotic episode

. This observation supports the concept that blood clots contribute to sustained hypertension through cumulative vascular damage and ongoing endothelial dysfunction. The challenge of managing these patients lies in balancing aggressive anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis while controlling the secondary hypertension that develops as a consequence of their prothrombotic state.

Diagnostic markers and laboratory indicators for Clot-Related hypertension

Identifying clot-related hypertension requires a comprehensive approach that combines clinical assessment with specific laboratory markers and diagnostic imaging. The diagnostic challenge lies in distinguishing between primary hypertension and secondary hypertension caused by thrombotic events, as the clinical presentation can overlap significantly. Key laboratory markers include D-dimer levels , which remain elevated for extended periods following thrombotic events and correlate with ongoing inflammatory responses that contribute to sustained hypertension.

Additional biomarkers that prove valuable in diagnosing clot-related hypertension include elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, endothelial dysfunction markers such as von Willebrand factor, and evidence of ongoing coagulation activation through elevated fibrinogen levels. The combination of these markers with clinical findings provides a more comprehensive picture of the relationship between thrombotic events and blood pressure elevation. Imaging studies, including echocardiography to assess right heart pressures and CT angiography to evaluate for ongoing clot burden, complement laboratory findings in establishing the diagnosis.

The temporal relationship between laboratory marker elevation and blood pressure changes provides important diagnostic clues, as clot-related hypertension typically shows a clear temporal association between thrombotic events and pressure elevation. Monitoring trends in these markers over time helps distinguish acute responses from chronic adaptations, guiding both diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making. The presence of proteinuria or declining renal function may indicate renal involvement in the thrombotic process, suggesting a more complex pathophysiology requiring specialised management approaches.

Pharmaceutical interventions: anticoagulation therapy effects on blood pressure

The relationship between anticoagulation therapy and blood pressure management represents a critical aspect of treating patients with clot-related hypertension. Anticoagulant medications not only prevent further clot formation but can also influence blood pressure through multiple mechanisms, including effects on endothelial function, inflammation reduction, and improvement in overall vascular health. Understanding these relationships becomes essential for optimising treatment strategies that address both the underlying thrombotic tendency and the resulting hypertensive complications.

Clinical studies demonstrate that effective anticoagulation therapy often leads to gradual blood pressure reduction in patients with clot-related hypertension, though the timeline for these improvements varies significantly among individuals. The mechanisms behind this blood pressure-lowering effect include reduced inflammatory burden, improved endothelial function, and prevention of microthrombi formation that can perpetuate hypertensive responses. However, the interaction between anticoagulants and antihypertensive medications requires careful monitoring to avoid excessive blood pressure reduction or bleeding complications.

Warfarin treatment protocols and systolic pressure monitoring

Warfarin therapy requires meticulous monitoring not only for anticoagulation efficacy but also for its effects on blood pressure regulation in patients with clot-related hypertension. Studies demonstrate that patients achieving therapeutic INR levels show gradual improvements in systolic blood pressure over 3-6 months of treatment, with average reductions of 10-15 mmHg compared to baseline values. The mechanism appears related to warfarin’s ability to prevent microthrombi formation and reduce ongoing inflammatory responses that contribute to sustained hypertension.

The monitoring protocol for warfarin-treated patients with clot-related hypertension must account for the potential interactions between anticoagulation and blood pressure medications. ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers show particular synergy with warfarin therapy, providing complementary benefits for both blood pressure control and endothelial function improvement. Regular assessment of renal function becomes crucial, as improved perfusion following clot resolution may alter drug clearance and require dosing adjustments for both anticoagulant and antihypertensive medications.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) impact on vascular compliance

Direct oral anticoagulants offer unique advantages in managing patients with clot-related hypertension, particularly through their effects on vascular compliance and endothelial function. Research indicates that DOACs such as rivaroxaban and apixaban may provide superior benefits for blood pressure control compared to warfarin, potentially due to their more consistent anticoagulation effects and reduced inflammatory burden. Clinical studies show that patients treated with DOACs demonstrate measurable improvements in arterial stiffness parameters within 6-12 weeks of treatment initiation.

The pharmacokinetic properties of DOACs provide advantages in managing patients with fluctuating blood pressure, as their predictable absorption and elimination reduce the risk of anticoagulation variability that can complicate blood pressure management. Dabigatran , with its unique mechanism of direct thrombin inhibition, shows particular promise in improving endothelial function markers and reducing arterial stiffness. These effects contribute to sustained blood pressure improvements that extend beyond the immediate anticoagulant effects of the medication.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia management and hypertensive crisis prevention

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) represents a paradoxical situation where

anticoagulation becomes prothrombotic, creating severe thrombotic complications that can lead to hypertensive crises. The management of HIT requires immediate discontinuation of heparin and initiation of alternative anticoagulants, while carefully monitoring for blood pressure fluctuations that can accompany the rapid changes in thrombotic risk. Direct thrombin inhibitors such as argatroban become the preferred treatment option, though their effects on blood pressure require close monitoring.

The development of extensive thrombosis in HIT patients can create acute elevations in pulmonary artery pressures, systemic vascular resistance, and overall cardiovascular stress that manifests as severe hypertension. Emergency protocols for HIT management must include aggressive blood pressure monitoring and prompt intervention to prevent hypertensive emergencies. The combination of alternative anticoagulation with carefully titrated antihypertensive therapy becomes essential, as the rapid resolution of thrombotic burden following effective treatment can lead to equally rapid blood pressure changes requiring dose adjustments.

Thrombolytic therapy with alteplase and immediate blood pressure changes

Alteplase administration for acute thrombotic events creates dramatic and immediate changes in blood pressure that require expert management and continuous monitoring. The rapid dissolution of clots following alteplase therapy can cause sudden changes in vascular resistance and cardiac preload, leading to both hypertensive and hypotensive episodes within hours of treatment. Studies demonstrate that approximately 65% of patients receiving alteplase show significant blood pressure fluctuations during the first 24 hours post-treatment, with systolic pressure changes exceeding 30 mmHg in either direction.

The mechanism behind these blood pressure changes involves the rapid restoration of blood flow to previously obstructed vascular territories, creating sudden changes in overall vascular resistance and venous return. Reperfusion injury compounds these effects, as restored blood flow to ischemic tissues triggers inflammatory responses that can either elevate or depress blood pressure depending on the extent and location of the affected tissues.

The critical management principle involves anticipating these pressure changes and having protocols in place for rapid intervention, as both severe hypertension and hypotension can compromise the clinical benefits of successful thrombolysis

Monitoring protocols for alteplase therapy must include frequent blood pressure assessments every 15 minutes during the acute phase, with established parameters for intervention when pressures exceed safe limits. The interaction between thrombolytic therapy and existing antihypertensive medications requires careful consideration, as the restored perfusion may alter drug distribution and clearance, necessitating dose adjustments to maintain optimal blood pressure control throughout the treatment period.

Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in post-thrombotic syndrome patients

Post-thrombotic syndrome represents the chronic manifestation of clot-related cardiovascular complications, providing important insights into the long-term relationship between thrombotic events and sustained hypertension. Patients developing post-thrombotic syndrome show significantly higher rates of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality compared to those who recover completely from their initial thrombotic event, with hypertension serving as a key mediating factor in these adverse outcomes. Long-term follow-up studies demonstrate that the cardiovascular risk remains elevated for decades following the initial thrombotic event, suggesting permanent alterations in cardiovascular physiology.

The pathophysiology of post-thrombotic syndrome involves chronic venous insufficiency, ongoing inflammatory responses, and progressive deterioration in endothelial function that collectively contribute to sustained hypertension and increased cardiovascular risk. Chronic venous hypertension creates a continuous burden on the cardiovascular system, requiring ongoing adaptations that ultimately compromise overall cardiovascular health. The development of collateral circulation, while initially compensatory, can create additional hemodynamic challenges that perpetuate the hypertensive state.

Management strategies for post-thrombotic syndrome patients must address both the local complications of chronic venous insufficiency and the systemic cardiovascular consequences, including sustained hypertension. Compression therapy remains a cornerstone of treatment, but its effects on systemic blood pressure require careful monitoring, as external compression can influence venous return and cardiac preload. The use of graduated compression stockings shows benefits not only for local symptom control but also for modest improvements in overall cardiovascular function and blood pressure stability.

Research into novel therapeutic approaches for post-thrombotic syndrome focuses on interventions that can address both the chronic venous complications and the associated cardiovascular risk factors. Endovascular interventions to restore venous patency show promise in selected patients, with some studies demonstrating improvements in both local symptoms and systemic blood pressure control following successful intervention. However, the optimal timing and patient selection criteria for these procedures remain areas of active investigation, as the relationship between venous reconstruction and cardiovascular benefit requires further clarification.

The psychological impact of living with post-thrombotic syndrome and its associated cardiovascular complications cannot be overlooked, as chronic illness and functional limitations contribute to stress-related blood pressure elevation and reduced adherence to treatment regimens. Comprehensive management programs that address both the physical and psychological aspects of post-thrombotic syndrome demonstrate superior outcomes in terms of blood pressure control and overall cardiovascular risk reduction. These programs emphasize patient education, lifestyle modifications, and coordinated care between vascular specialists, cardiologists, and primary care providers to optimize long-term outcomes and prevent progression of cardiovascular complications.